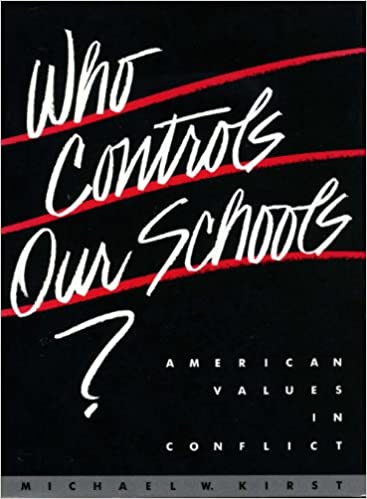

Eighth Installment: Who Controls Our Schools? The Genesis

"Conversations With and About Mike"

Photo courtesy: Stanford Alumni Association

Mike Kirst, Dartmouth’s Class of 1961 Reunion Yearbook

As the coronavirus pandemic has spread across the world, federal, state, and local officials in the U.S. are not only arguing over what to do but also over who has the authority to do it. As of the writing, in the spring of 2020, nearly all public and independent schools are closed in this country due to this global calamity. How and when American schools will reopen, and who will make that decision, are widely debated, prompting us to recall Mike’s most widely read book—Who Controls Our Schools?: American Values in Conflict, published in 1985. 1

In this installment, we explore how early in his studies, Mike began to formulate this question and eventually answer it in a way that demonstrates its complexities—which will help us to understand better the “Who’s in charge of American schools” question in this pandemic era.

When we last left Mike back at Dartmouth, he had just completed a key summer internship in Washington, D.C., arranged by Martin Segal, his Dartmouth economics professor, and mentor (Click on Installment 7 for details). Based largely on that internship, Mike decided not to pursue an MBA and, instead, focused on coursework in economics and government. He also pondered where to attend graduate school for preparation to be a “career” public servant.

Clip 1: Three Dartmouth faculty “pound on me: ‘Don’t go to Syracuse! Go to Harvard!”

Knowing now what we do about Mike’s career, his side comment that the public service preparation “might have included state-level” is worth noting, though he admitted at the time that he knew very little about state-level government work or governance when deciding to attend Harvard for grad school.

When asked, however, to name who most influenced his thinking at Harvard, he immediately commented on two professors whose area of expertise was state government: V.O. Key and Sam Beer…but primarily V.O. Key.

Let’s listen in:

Clip 2: V.O. Key stimulates a focus on state politics, cultures, and “characters.”

Valdimer Orlando Key, Jr., leading American political scientist. (Photo courtesy of Cornell University’s Roper Center)

Valdimer Orlando Key, Jr.’s Southern Politics in State and Nation is considered a “classic in regional studies,” pioneering the use of quantitative techniques. Prior to teaching at Harvard (from 1951 until his death in 1963), he had taught at Johns Hopkins University and served with the U.S. Bureau of Budget during World War II. 2 “V.O.” Key, as Mike calls him, not only introduced Mike to the study of states and state culture but also served as a role model who tacked successfully between academic and public service, with an emphasis on the role of finance and budgeting on policymaking and implementation.

Samuel Beer, Harvard professor, expert of American Federalism. (Photo courtesy of Harvard Magazine)

Professor Key sparked what was to become Mike’s interest and eventual expertise in state finance, policy-making, and reform—both as an academic and confidant to key governors and other state leaders across the nation and across time.

Mike also mentions Samuel Beer, another Harvard professor who “did state politics.” Professor Beer joined Harvard’s faculty after completing military service in 1946 and was one of Harvard’s “most popular and iconic professors,” and whose To Make a Nation: The Rediscovery of American Federalism became a textbook for the study of American political theory.3When describing his program of study in Harvard’s Public Administration program, Mike also talks excitedly about the opportunity to be with older, experienced civil servants, especially those with military backgrounds:

Clip 3: Most Harvard classmates were civil servants, older, and some in the military.

Another key influence at Harvard was John Thomas Dunlop, Mike’s “chief advisor for economics,” then chairman of the Economics department. Later Dunlop served as U.S. Secretary of Labor under President Gerald Ford as well as a highly placed advisor in the administrations of Presidents Carter, Reagan, Bush, and Clinton.

Let’s listen in as Mike describes that relationship and Dunlop’s being “buddies with all these labor union guys.”

Clip 4: John Dunlop: Mike’s economics advisor, U.S. Secretary of Labor, and “buddies with labor union guys…some of them ‘unpolished characters,’ let’s say.”

John Thomas Dunlop, Industrial Relations System Expert

Dunlop remained on the Harvard faculty his entire career and, even after retirement, staying active in research and teaching including leading freshmen seminars at the age of 85 (as has Mike after his retirement from Stanford in 2007). In addition, Dunlop regarded himself as “fundamentally a problem-solver with an abiding interest in the workplace” (which can be said of Mike as well about the classroom). 4 He was recognized as a faculty member whose cadre of doctoral students became leaders in their fields, including “prominent industrial relations specialists, labor historians, and labor economists.” 5 (Again, the same is often said of Mike.)

We also see from his Harvard experiences the seeds for Mike’s accomplishments in both academic and government circles, drawing on diverse disciplines from the business and public administration departments. Notice Mike’s delight in the next clip as he describes successfully negotiating with his professors, V.O. Key and John Dunlop, to approve this “portmanteau approach” to his doctoral degree: a Ph.D. in Political Economy and Government. Let’s listen in:

Clip 5: “When you combine the disciplines like this, you’ll never…teach in college.”

In addition to the irony of his being told he’d never be able to teach in college (due to that two-pronged doctoral degree), Mike also reminds us in an interview for the New York State Archives 6that he never took an education course, as we hear below.

Clip 6: “The first course I had in education was the one I taught at Stanford.”

Mike describes the origin of his dissertation topic as he elaborates advice from a Harvard professor who had formerly been the director of legislation at the National Institute of Health (NIH):

Clip 7: Dissertation Topic from Director of Legislation at NIH becomes Mike’s first book: Government Without Passing Laws.

Arthur A. Mass, professor of government. (Photo courtesy of The Harvard Crimson

Mike’s advisor for his dissertation was Arthur A. Mass, a longtime Harvard government professor and then chair of the Department of Government. Mike writes in the Acknowledgements section of the book that “Without the encouragement and counsel of Arthur Mass, I would never have completed the study. His assistance was invaluable and his impress is on almost every section.” 7

Mass’s doctoral dissertation examining the development of U.S. water resources also led to his first book, Muddy Waters: The Army Engineers and the Nation’s Rivers, which was “an analysis of an of an ‘iron triangle,’ its dysfunctional consequences and scheme of reform…reveal[ing] complex networks of influence among interest groups, congressional committees, and bureaucratic agencies.” 8These concepts are all especially central to Mike’s earlier writings and teaching at Stanford.

Mike’s stories about his years at Stanford, early research, and writing give us insight into his developing appreciation of the complexity of public policy, its transformation as implemented by different agencies and levels, and its enforcement by varying forces and players. He offers two powerful metaphors to illustrate these complexities.

Mike wrote Who Controls Our Schools as he was serving as president of the California State Board of Education, a state educating one of every eight American school children. He notes, “[n]either the word ‘education’ nor the word ‘school’ appears in the Constitution of the United States. Because the framers chose not to include education among the functions of the federal government, the provision of schooling is a power reserved to the states.” 9

He highlights related complexities, though, observing, “[f]ew components of American political ideology are as firmly ingrained as local control of schools” and that while “[a]s a principle, local control remains unchallenged,” still “the growing influence of centralizing forces—state and federal authorities courts, national testing agencies, and national interest groups—has made ‘home rule’ now more illusion that actuality.” 10

Two Metaphors Mike Offers to Understand “Who Controls Our Schools?”

1. State Policy-Making as a “Spice Cabinet”

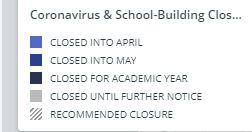

In the recent edition of their most widely-used textbook for the politics of education, Mike and his co-author Fred Wirt observe, “If variety is the spice of life, education decision making in the fifty states is a veritable spice cabinet.” 11A modern-day example of the state’s predominant role in American schools and this variety, the map below shows the “spice cabinet” of approaches states have taken in closing schools (as well as, of course, the variety of actors and processes for reaching such determinations) and signaling intentions for re-opening in the spring of 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S.

State-by-State Map of School-Building Closures

Interactive map courtesy of Education Week, April 26, 2020 Sources: Staff reporting; National Center for Education Statistics; government websites and communications

Click this link to enlarge

Note that as of April 19, 2020, some states had closed schools until further notice, some for the rest of the school year, some just until April, some until May, and one at that point not at all.

2. Three Policy-Making Areas in Public Education as a “Marble Cake”

In Who Controls Our Schools? (1984), Mike trades his president of California’s State Board of Education hat for one of an academic and political scientist, and reminds us that America’s schools are a “political system” with “everybody and nobody in charge.” 12

Mike Kirst and Fred Wirt’s most recent textbook for the study of the politics of education.

Wirt and Kirst note in updated editions of their politics of education textbook that “the system is so dynamic it cannot be understood by such [simple] concepts as top-down and bottom-up.” Instead, they argue that “federal politics [in education] operates within an intergovernmental context whereby higher levels of government try to get lower levels to change policies and practices,” 13 and in which there “is no distinct compartmentalization of sovereignties and powers among the three levels of nation, state, and locality, but in an interlocked pattern of cooperation and conflict.”14 Of the three images, they offer to understand the concept of “federalism” in the American system of public schools today, one is particularly useful in today’s pandemic context.

They label it “the marble cake” metaphor and explain that “The marble cake [as opposed to a three-layer cake] recognizes that the federal, state, and local levels are not distinct, and policy spills over from one level to another.” 15

Powerful images such as these developed and rediscovered over time help us to better understand how nuanced the “who controls our schools” question is as states in the coming weeks/months make complex decisions about how and when to open schools, thereby fulfilling the “provision-of-schooling” powers constitutionally reserved to them within our federal system of governance.

“Dr. Kirst Goes to Washington,” the next installment of this biography project, will document how Mike carried forth many of Maass’s policy perspectives and approaches to his career as well as those of the other triumvirate of Harvard influencers noted in this installment. We will also learn about some important personal developments in Mike’s life while at Dartmouth, Harvard, and in his early years in D.C.

Stay tuned.

Editor’s Note: The Appendix for “Conversations With and About Mike” contains transcripts for the recorded audio and video clips. To view the Audio Transcripts go to this page >

Footnotes

- Kirst, M. W. (1985). Who Controls Our Schools: America Values in Conflict: Values in Conflict. Palo Alto, California: Stanford Alumni Press.

- Encyclopedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/VO-Key-Jr (updated 3/9/2020).

- Grimes, W. (2009, April 18) “Samuel H. Beer, Authority on British Government, Dies at 97,” The New York Times. Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/19/us/19beer.html (accessed 4/25/9/2020).

- Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Thomas_Dunlop (updated 3/9/2020).

- Sullivan, P. (2003, October 4) “Labor Secretary John Dunlop Dies; Harvard Professor, Negotiator,” Washington Post.

- Mike Kirst interview with Anita Hecht, November 19, 2013, for The New York Archives: States’ Impact on Federal Education Policy Oral History Project.

- Kirst, M.W. (1969). Government Without Passing Laws: Congress’ Nonstatutory Techniques for Appropriations Control. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press.

- Mansfield, H., Cooper, J., Hoeber, S., & Beer, S. (2007). A Memorial Minute from the Minutes of Meeting of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, 5/15/2007 https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2007/06/arthur-maass/ (accessed 4/25/2020).

- Kirst, M.W. (1984). Who Controls Our Schools: America Values in Conflict: Values in Conflict. Palo Alto, California: Stanford Alumni Press, p 95.

- Kirst, M.W. (1984), p. 97.

- Kirst, M.W. & Wirt, F. (2009). The Political Dynamics of American Education. Fourth Edition. Richmond, California: McCutchan Publishing, p. 232.

- Kirst, M.W. (1984), p. 14.

- Kirst, M.W. & Wirt, F. (2009), pp. 369-370.

- Wirt, F. & Kirst, M.W. (1975). Political and Social Foundations of Education. Berkeley, California: McCutchan Publishing, p. 148. The other two metaphors of intergovernmental relations in the federal

governance of U.S. education—the “picket-fence” and the “ecology of games”—will be discussed in future installments when discussing the development and implementation of categorical programs, unfunded mandates, and related federal and state education programs. - Kirst, M.W. & Wirt, F. (2009), p. 369 and Wirt, F. & Kirst, M.W. (1975), p. 148