13th Installment: The “Accidental Professor” Era Commences

"Conversations With and About Mike"

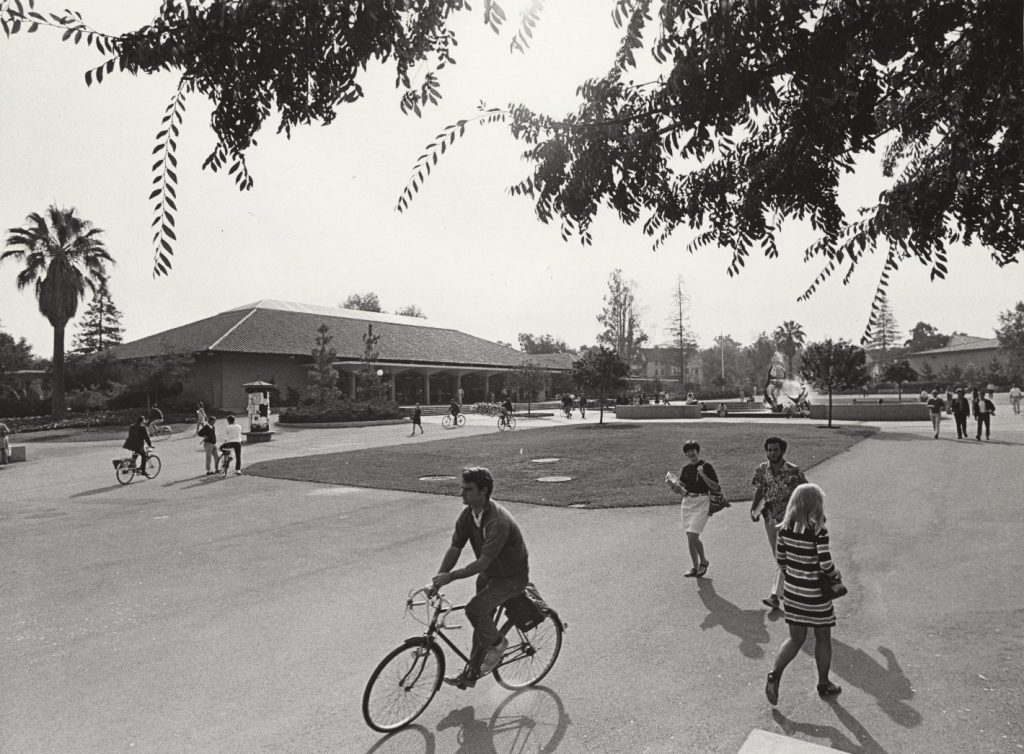

Stanford Campus, circa 1968-1969, White Plaza, near the university’s School of Education building, Cubberly Hall. Photo courtesy of Stanford Archives.

The Reluctant Academic and Californian

Nine years after Mike had retired from serving as a professor at Stanford University and had transitioned to Emeritus status, the university’s Emeriti Council invited him to reflect on his nearly half-century-long professional career.

He begins that Spring 2014 presentation telling of an exchange he had with his Harvard doctoral studies committee decades earlier:

Audio Clip 1: Mike, “I don’t ever want to teach, and I’ve never thought about being a professor.” (0:37) 1

And as we know from Installment 9, after completing his doctorate in 1964 with a dual degree in Political Economy and Government, Mike headed off to Washington D.C. to pursue his dream of becoming a public servant just as thought leaders such as John Gardner were helping the newly appointed President Lyndon B. Johnson to formulate his plans for a major expansion of the federal role in education as part of his “War on Poverty,” just months after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

At the outset of this Autobiographical Reflections presentation for the Emeriti Council, Mike, with characteristic wit, identifies the first stage of his Stanford career as the era of “The Accidental Professor.” He also describes how he felt about leaving D.C. Let’s listen in:

Audio Clip 2: Mike, “I came out here [to California] as an absolute last resort and wanted to leave as soon as possible.” (0:12) 2

As we have heard in an earlier installment, during Mike’s final two years in Washington, he had served as the staff director of the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Employment Manpower and Poverty headed by the Democratic Senator from Mike’s home state of Pennsylvania. Mike would later relate to the Stanford Oral History Society, “I loved that job,” 3 and thought it was “a really good career.” However, as he explains to this Emeriti Council gathering:

Audio Clip 3: “And lo and behold Senator Clark loses….” (0:36) 4

So, after the committee chair explains that he has to clear out of his office in six weeks, Mike realizes that by aligning with a Democratic senator, he had cut off many previously considered avenues to other DC positions. Mike summarizes: “I had gotten out of civil service and become political.” Not only had Clark lost his Senate seat, so had another Democratic senator, Wayne Morse, who had promised Mike a staff position on the Senate education committee as a backup in case Clark lost.

From Loss to Opportunity—with Luck and Strategy

Henry “Thomas” James, Dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education, hired Mike Kirst. Photo courtesy of the James family.

Richard Nixon in that 1968 presidential election beat Hubert Humphrey. So Mike recalls that “I could not get anything decent” in D.C. while also realizing “I was twenty-nine years old with two children.” All of this happened when his son Chip was seven and his daughter Ann, one. In addition, he and his first wife 5 had purchased a home in McLean, Virginia, a nearby suburb of D.C.

We hear a bit of relief in Mike’s voice when at the end of this clip he says, “I remembered this contact I had from Thomas James,” then Dean of Stanford’s School of Education, who had met with Mike in D.C. before the election, attempting, even then, to recruit Mike to come to Stanford.

Recognizing his conundrum, Mike re-contacts Dean James after the election, saying, “If you’re still interested, I’m very available.”

According to Mike, the dean replied, “Come on out.” And Mike flew out to California for a follow-up interview, still maintaining, however, that even if he got the Stanford job, he’d go back to D.C. once the Democrats were back in power.

In a recent interview, Mike explained to me the details and his thoughts about what turns out to be this seminal set of conversations with Dean James and his advisers. Let’s listen in:

Audio Clip 4: Mike, “When [Dean] James was recruiting me” to Stanford…. (2:11) 6

There’s a lot to learn and unpack from that conversation, including:

Tim Wirth, former assistant dean at Stanford School of Education. Photo courtesy of Stanford Historical Society.

- What Dean James was looking for in reaching out to Mike: This was primarily Mike’s then fairly unique experiences as a base for teaching federal and state education policy and the politics of school finance reform (documented in Installment 9).

- Who had suggested to the dean that he should try to recruit Mike: That would be a former White House Fellow, Tim Wirth, who then was the associate dean in the School of Education (and later served in the House of Representatives (1975–1987) and U.S. Senate (1987–1993) from Colorado) and one other White House Fellow, Tom Cronan—showing again the continued importance of Mike’s leading the D.C. Fellows program during the early years of his being in D.C. (detailed in Installment 9).

- That Mike’s decision during his senior year at Dartmouth to enroll in a dual MBA/MA program (revealed in Installment 7) caught the dean’s attention when he was reviewing Mike’s resume.

- The 1968 meeting with Dean James was the first time Mike met James Kelly who first introduced Mike to his wife Wendy (covered in Installment 10), now of more than four decades. We will hear further in this and subsequent installments how important Kelly was for Mike, as a friend, a colleague, and a key funder of his research and related consulting projects in key states as well as nationally and internationally for the better part of Mike’s Stanford years.

Mike makes it quite clear in this clip that before the results of the 1968 elections came in, he “wasn’t really interested” in becoming a professor at Stanford and actually had never given the matter of teaching at a university much thought. Further, at the time, he felt Stanford was “a long way away” from D.C. and that “being a professor…just sounded like it was not very interesting compared to all the interesting stuff we were doing [in D.C.].”

But as we heard earlier in this installment, Mike changed his tune when he found out after the election that there were few, if any, comparable opportunities for him after the election in D.C.

The Birth of a “One-of-a-Kind” Program at Stanford

Even at their initial dinner in D.C., Dean James had been particularly fascinated by Mike’s enrollment in Dartmouth’s “three/two year” MBA program offered through the Tuck School of Business. 7 Even in this initial discussion, the dean “thought this was really unique.”

Ernest C. Arbuckle, Dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Business, 1958-1968. Photo courtesy of Stanford Archives.

So, when Mike took up Dean James on his offer to come out and visit Stanford, the dean returned to this aspect of Mike’s background and included the then-dean of Stanford’s business school, Ernie Arbuckle, in the conversation.

From these initial discussions blossomed the idea of a joint MA – Education/MBA program that allows students to simultaneously pursue an MA at the Graduate School of Education (GSE) and an MBA at the Graduate School of Business (GSB). The MA/MBA joint degree program they created was developed into a two-year, full-time program that integrated a comprehensive set of MBA classes with education coursework, resulting in a novel educational management curriculum, unique at that time. In 2021 Stanford celebrated the 50th anniversary of the first graduating class from this dual-degree program in 1971. 8

Even though Mike dropped out of the Tuck School of Business during his senior year at Dartmouth to start graduate studies in public administration at Harvard, he was still able to draw on the basic design of that program to operationalize what the two Stanford deans had wanted to create. They were interested enough in this design that they offered, and Mike accepted, a joint position as a professor of education, with a courtesy appointment in business administration and as affiliated faculty in political science and public policy. (See Mike’s resume for details.)

Chester Finn, senior fellow and president emeritus at the Thomas F. Fordham Institute, recently commented how unusual such a joint appointment is and how much it benefits Mike’s students and his research. Finn believes that this dual appointment gave Mike “two perspectives” that he could “harmonize” and “use each to enhance…the other.” And he explains in this clip why he has recommended to so many “young people who say they want a future in education go check out that dual program Mike Kirst runs at Stanford.” Let’s listen in:

Audio Clip 5: Checker Finn: “I’m not aware of anybody…who’s pulled off that kind of double play.” (1:19) 9

This “academic coalition building” across departments even as he was beginning his faculty position in Palo Alto would foreshadow his emphasis on those tactics to his students during his four-decade tenure at Stanford. In addition, it foreshadows his own successful approach to advancing public policy reforms, beginning during his start-up years at Stanford in Florida and Oregon (detailed in this and the upcoming installments) and most especially in California.

This dual program was part of a bigger design Dean James envisioned for Stanford’s school of education in the 1960s. He planned to find, attract, and hire disciplinary scholars (i.e., political scientists and economists) and apply their scholarship and work to education. More specifically, for Mike, the dean had a strong interest in new emerging fields, such as federal education policy and the politics of such policy, neither of which had been much of an issue until President Johnson signed into law in 1965 the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), from which Mike had developed considerable first-hand understanding and experience (as detailed in Installment 8 and Installment 9).

The planning of this MA/MBA program helped Mike even at the start of his Stanford years attract federal and foundation funding to the university for training and research projects with other major universities including, for example, The University of Chicago. And these research grants in those early years led, in turn, to his initial consulting with states such as Florida and Oregon to help them examine and improve their school finance approaches, at a time when states began playing a major role in financing America’s K–12 education. 10

Mike explains these linkages as well as the start of his key relationship with Jim Kelly. Let’s listen in:

Audio Clip 6: Mike, “The Ford Foundation funded a bunch of educational administration programs that were trying to shake up the field. The Stanford MA/MBA program was one of them.” (1:54) 11

Dr. Edwin Bridges, Stanford Professor at the Graduate School of Education, 1974-1999. Photo courtesy of Stanford Archives.

For this biography, two more personal points are worth noting while listening to this clip.

First, Mike’s initial encounters with Jim Kelly occurred before Jim started at the Ford Foundation while he was a faculty member at Teachers College and playing a leadership role at the Urban Coalition. It was there that he worked with Mike’s second wife, Wendy Burdsall Kirst; and he later arranged Mike and Wendy’s first date.

Second, we hear Mike mention Edwin (Ed) Bridges, who at that time headed the educational administration program at The University of Chicago. He later joined the faculty at Stanford and occupied the office adjoining Mike’s in Cubberly Hall. The two also shared an office assistant, Eve Dimon, for more than four decades. Dr. Bridges was my academic adviser at Stanford and Dr. Kirst, my dissertation adviser. Mike maintains this same office, now as an emeritus professor, in Cubberly Hall, Room 121, after more than half a century.

First Few Years as “Accidental Professor”

Plunging Into Academic Publishing and Bringing In Funding

Mike initially may have been reluctant to come to California, but when he landed on his new academic terra firma in Palo Alto, he jumped in with both feet—as an academic writer, researcher, teacher, and adviser. He designed and taught a series of new courses on the then embryonic field of the politics of education. He also attracted important funding for the university.

In December 1969, shortly after his arrival at Stanford, Mike and Edith K. Mosher, a professor at the University of Virginia, published the seminal piece in this new field. Review of Educational Research, the respected juried academic journal, carried their article, “The Politics of Education and Research Methodology.” And they advised fellow scholars and policy students that “gone are the days of minimal state involvement in education” as well as that “today’s educator must understand the workings of government, politics, and public finance.” 12

During his first three years at Stanford, Mike wrote and published close to a dozen articles, analyses, and book chapters for:

- organizations such as the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity, U.S. Commission of Civil Rights, the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education, and Educational Testing Service;

- academic and education journals, including Education and Urban Society, Review of Educational Research, and Phi Delta Kappan; and

- published books such as a chapter in Benjamin Rosner’s The Power of Competency-Based Teacher Education.

Within a year—or as he likes to phrase it—”right off the bat,” Mike served as editor for his first published book as a Stanford professor, which was a compilation of what he found to be the most relevant politics of education publications to date: The Politics of Education at the Local, State, and Federal Levels published in 1970 by the academic publishing arm of McCutchan Press.

By 1972 Mike had also co-authored, with American political scientist Frederick Wirt at the University of Illinois, the first edition of what many consider to be the definitive textbook in the field of education politics entitled, The Political Web of American Schools. The content of this widely used textbook was initially published by Boston’s Little Brown Press and then later revised and republished by McCutchan in 1974 as The Political and Social Foundations of Education with several other updates, the most recent in 2009.

First of many updates to the Mike Kirst and Fred Wirt politics of education textbook. Photo: Dick Jung.

Fred Wirt & Mike Kirst, published 1972. Photo: Dick Jung.

By 1974, four of the 15 books listed on his resume had been researched, written, and published by an array of academic publishing houses. They include, as reflected in Mike’s resume:

- Federal Aid to Education: Who Governs, Who Benefits (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1972), with Joel Berke

- State, School and Politics, Editor (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1972)

- The Political Web of American Schools (Boston: Little Brown, 1972), with Frederick Wirt. Revised in 1975 and republished as Political and Social Foundations of Education (Berkeley: McCutchan)

- Revising School Finance in Florida (Tallahassee: Florida Governor’s Office, 1973), with W. Garms

Quite a prodigious out-of-the-gate publication record, especially for “an accidental professor”!

Earlier this month (July 2021), when receiving the prestigious James Bryant Conant Award from the Education Commission of the States for “his unwavering commitment to improving school finance systems to serve students more equitably,” Mike spoke about the significance of what he and Walter Garms produced as part of his early Ford Foundation-funded school finance work in Mike’s first few years at Stanford (which we heard about at the end of the previous audio clip).

Photo courtesy of Education Commission of the States.

In the audio clip below, we hear about this early research and writing as the genesis of Mike’s school finance and governance work across several states over the years and decades later in California as Governor Brown’s State Board of Education president:

Audio Clip 7: Mike on his work in 1973-74 on the Pathbreaking Florida Education Finance Program (0:13) 13

Mike speaks in this clip of The Florida Education Finance Program (FEFP), which the Florida legislature established in 1973 based on Mike’s early Ford-funded research at Stanford. It has lasted for more than four decades as the primary mechanism for funding the operating costs of Florida school districts, including both charter schools and traditional public schools.

Recently Mike reflected on this early work in Florida to the members of the current California State Board of Education, saying in this clip, “I would say that’s one of the best things I’ve ever done. We did a total overhaul of the finance and education program there.” And, “It still lasts in Florida.”

In both states, the approach for funding districts is based on a sophisticated and rational weighted funding formula to help guarantee that students have access to services appropriate to their educational needs. Both incorporate accountability measures, as well, to drive local planning and assessment of educational services.

Mike Takes His Experience and Expertise into His Initial Teaching and Advising Roles

Mike’s experiences with policy-makers, reflected in his research and publication work, formed the bedrock for the courses he taught at the start of his tenure at Stanford. Mike’s courses in these early years focused on the ascending federal and state role (especially in finance and governance) that had previously been controlled by more than 16,000 local school boards, the politics of education policy development and implementation, and the use of social science research frameworks in educational research methodology.

His teaching role also included designing and teaching a seminar for doctoral students on conducting political research, which led to his serving as dissertation adviser for many of them. In addition, Mike served as the academic adviser for many of the students in the joint MA/MBA program he created, adding up to a sizable advising role. Looking back, Mike estimates that he served as an academic or dissertation adviser on average for 10–15 students at any one time in those early years. 14

And when holding down these new teaching and advising roles, Mike was traveling rather frequently for his research, consulting, and course-building work.

In addition to his work in Florida, his consulting during these initial years at Stanford took him frequently to D.C. during the preparation of a special school finance report for the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity chaired by Walter Mondale. Mike quipped once, “Thank God for all those flights” back then “that left San Francisco at three in the afternoon on Wednesday and returned on Friday afternoon” for him to be able to juggle all that he was doing in those first three years at Stanford. 15

Up Next

Our next installment advances the clock to learn from Mike’s pioneering reform efforts in Oregon, Texas, and other states. The next installment also will provide a personal account of how Mike Kirst initially met Jerry Brown when he was gearing up for his first run as California’s Governor (1977–1983) and how the now-famous tax-revolt referendum Proposition 13 “blew up” their planned education finance reform initiatives for both of Brown’s early terms as Governor of California. 16

Stay tuned then and join us again for Installment 14 coming out later this summer.

Editor’s Note: The Appendix for “Conversations With and About Mike” contains transcripts for the recorded audio and video clips. To view the Audio Transcripts go to this page >

Footnotes

- Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks. stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

- Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks. stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

- Mike Kirst interview with Diana Diamond, January 28, 2013, for the Historical Society Oral History Program Interviews (SC0932). Department of Special Collections & University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries & Academic Information Resources, Stanford, California. https://purl.stanford.edu/pq707sp4393. - Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

- Seven years earlier in 1961, Mike had married Janet Elliott immediately after earning his A.B degree in Economics from Dartmouth University.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, March 5, 2020.

- The “Three/Two MBA Program” in Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business allowed students with outstanding undergraduate grades to start the 2-year MBA set of prescribed courses after their junior year, with the opportunity to earn an MBA degree only one year after earning a bachelor’s degree.

- Stanford University’s Business School website: https://ed.stanford.edu/academics/masters/mba

- Checker Finn interview with the author, October 25, 2018.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, June 30, 2021.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, June 30, 2021

- Mosher E. (November 1980). Politics and Pedagogy: A New Mix. Educational Leadership, 38(2), pp.110-11. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ236653

- Mike Kirst’s remarks at the California State Board of Education Meeting, July 14, 2021.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, June 30, 2021.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, July 16, 2021.

- Proposition 13 was an amendment to the California Constitution passed by voter initiative in June 1978 that limited property taxes, until then the major source of school funding. See EdSource’s glossary for further explanation: https://edsource.org/glossary/proposition-13