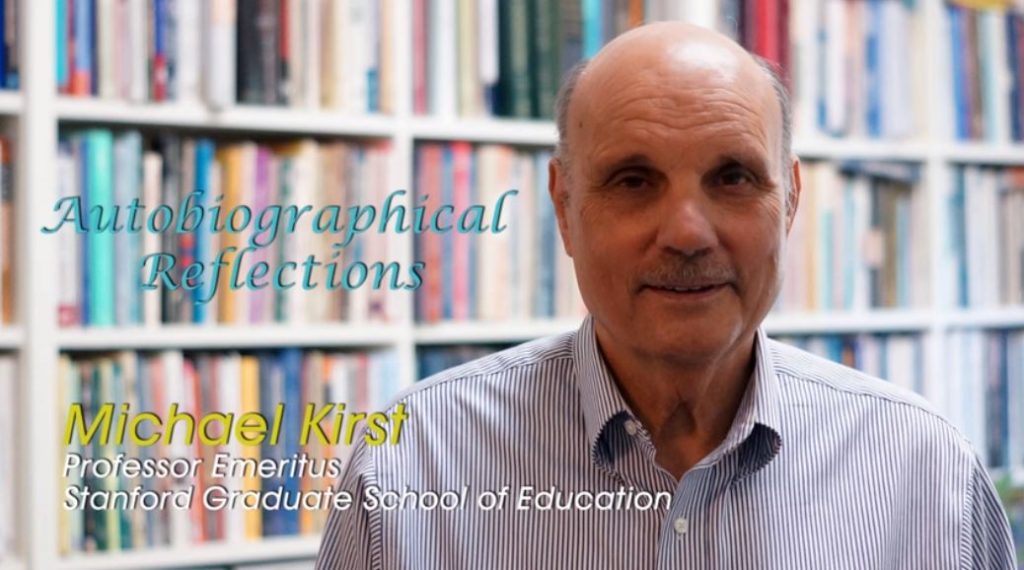

Sixth Installment: Early Influences, Part 1

"Conversations With and About Mike"

Photo courtesy of Stanford Emeriti Collection.

“Perhaps more than any genre, nonfiction has been changed by the Internet, which turns a biography or history book into a series of fascinating leads.” The New Yorker. September 2, 20191

Early Influences: Part 1

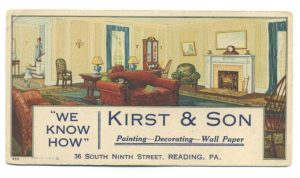

Antique Ceramic Advertising Button.

“Amazing…I never saw any of these before!” Mike Kirst noted in response to five images I sent him from my internet research using the search term “Kirst & Son.”

As shown on this advertising button, “Kirst & Son, Beautifiers of Homes” was the residential painting, decorating, and wallpaper firm in downtown Reading, Pennsylvania, established in 1867 by Mike’s grandfather, and owned and operated by Mike’s father, Russell John Kirst, when Mike was growing up.

Mike’s grandfather died when Mike was young, and Mike reports that he mostly recalls that his grandfather “had a bar in the basement of his house on South 5th Street, Reading, and I used to deliver the beer to his friends at his parties.” Mike continued, “Maybe that was good preparation for Dartmouth.”

More on Dartmouth later in this and subsequent installments.

A Bit of Background

Although neither Mike nor his brother ever worked for Kirst & Son, the impact of it and growing up in Reading, Pennsylvania in the 1940s and 1950s is clear, as you’ll hear in Mike’s recollections from that time.2

Let’s first listen to Mike’s story of Reading, his early schooling, and his initial college aspirations.

Downtown Reading, Pennsylvania in the 1950s.

Clip 1: Pennsylvania’s Coal Country and Initial College Thoughts

The Ricks and the “Silents”

An advertising blotter for the company of Mike’s father and grandfather uncovered in the internet search and a surprise to Mike.

As with most things, Mike tends to be rather parsimonious when talking about his childhood in this or other autobiographical reflections recorded for Stanford and others. For example, it takes Mike less than a minute and twenty seconds during this hour-long Autobiographical Reflections to cover about 18 years of his life—from his birth in 1939 to attending college in 1957.

When asked recently to name “one or two ways you feel your Mom and Dad influenced you the most,” he began “Well, my father did graduate from college. He went to Gettysburg College and that’s where my older brother went…. And so, you know, Dad had a college background. And so that was an influence. And he talked a lot about that. And he took us to sporting events…. And so I had a general orientation to what it [attending college] was about. And so that was helpful from that standpoint.”

Mike’s reply about his mother was more expansive: “My mother was related to an illustrious family in Reading named ‘Rick,’ and my father didn’t make that much money in his business, but some of the Ricks did. So I had all these relatives, and they went to college…. The original Ricks came over in the 18th century to Berks County, Pennsylvania. And he was a minister. So ministers must have been among the top two percent of educated people in the 18th century…. And so that side of the family produced some strong academic people,” he told me.

Being the son of parents with college and professional backgrounds placed Mike, born August 1, 1939, and his older brother John, three years his senior, in a different circumstance—academically if not economically—than their peers in the “Silent Generation,” generally defined as individuals born in the U.S. between 1928 and 1945. Those who have written about the Silent Generation note, “These were children of The Great Depression whose parents…faced economic hardship and struggled to provide for their family.”3 Further, unlike the previous generation who had fought for “changing the system,” the Silent Generation were about “working within the system.” They did this by keeping their heads down and working hard, thus earning themselves the “silent” label.

As we’ll see in more detail later, these themes of working hard, keeping one’s head down, working within the system, and helping lead—often behind the scenes—in the civil rights movement resonate with observations from others about Mike’s character, M.O., and values (highlighted in earlier installments of this series, for example, The Best Years of a Career and Three Lessons from a Long Career).

A Big Turning Point

Mike describes more about his family and his admission to Dartmouth College in a recent conversation when asked how that materialized.

Clip 2: Admission to Dartmouth: A Big Turning Point

Recruited to Dartmouth as a Football Center

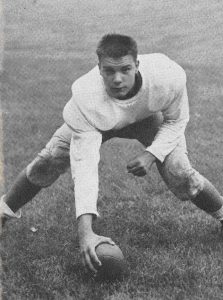

Mike pictured as a center for his high school football team circa 1957. Photo courtesy of Stanford University.

Mike’s principal at Wyomissing High School played an active role in his college exploration. Mike had also been admitted to Wesleyan College, which his high school principal thought “was great…because [he knew] I was interested in public affairs, and he had some knowledge of their political science department.” This principal also met with the assistant football coach from Dartmouth and discussed Mike’s academic record. Based on that visit, Mike continues, “they then began recruiting me for football at Dartmouth.”

With a somewhat uncharacteristic “Wow,” Mike reveals his reaction to being recruited to a team that good (third in East Coast college football) and having Dartmouth’s assistant coach travel all the way to his high school to recruit him.

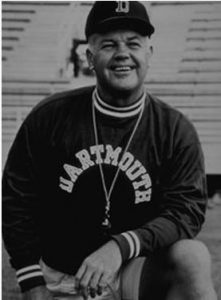

To this day, Mike speaks with pride about the head coach of Dartmouth’s football dynasty at the time: Robert L. Blackman. Known among players and students as “The Bullet,” Bob Blackman served as head football coach at the University of Denver, Dartmouth College, the University of Illinois, and Cornell University. Blackman had an astounding 104-37-3 record in his 16 seasons as head coach at Dartmouth from 1955 to 1970 and led Dartmouth to its first conference title in 60 years in 1958, during Mike’s early years at the university.4

Robert Blackman, “The Bullet,” inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a coach in 1976. Photo from Wikipedia.

The most important point about this clip is how Mike starts and finishes these recollections about Dartmouth’s first contacts. “Yeah,” Mike says, “I do remember this because this was a big turning point.”

When asked about what this Dartmouth opportunity meant to him, Mike replied forcefully: “Well it just elevated my ideas. I mean it changed my whole vision of what kind of colleges I could attend.” Mike then reflects on some of his later experiences at Dartmouth and even his next step into his doctoral studies at Harvard University. For example, he explains, “a lot of professors at Dartmouth came from Harvard [including Dr. Segal, Professor of Economics at Dartmouth, who we hear more about later in this installment] and so their whole vision was ‘you belong at Harvard as a graduate student.’ I don’t think that would have been if I went to Gettysburg or something.”

Mike concludes, emphasizing that his Dartmouth experience “just elevated the game in my mind as to what I could be and where I could go. So, you know, it was like a dream.”

A Dream Derailed, Almost

But this dream almost did not happen. Mike adds that he was initially put on Dartmouth’s waitlist and posits why.

In hearing what Mike describes as a “very interesting story,” we also learn the origin, perhaps, of his strong negative views to this day about the SAT and other standardized aptitude tests. Let’s listen in:

Clip 3: Mike’s “Interesting Story” Placement on Dartmouth’s Wait List

A Couple of Takeaways

Here again were Coach Blackman and Mike’s high school principal supporting his admissions process for Dartmouth (and Wesleyan’s admission director, too).

We also experience Mike’s talent as a storyteller. That ability to communicate simply, sometimes through telling anecdotes, will become increasingly clear via this biography project to be an essential part of Mike’s successes as a teacher, writer, education reformer, and a sort of politician himself.

Even the way he fumbles a bit in pronouncing “analogies” and punctuates his narrative with his voice going up an octave, and claiming in a tone of disbelief, “I’d never seen questions like this: ‘fish is to cat as [cat is] to dog!” resonates Mike’s early mistrust of aptitude testing that had “nothing to do with what I studied” in high school, in contrast with the afternoon’s achievement test where he excelled “on things (he) had studied in school.” He concludes, “Ever since then, I’ve frankly been leery of the SAT as a good measure of what you know.”

In subsequent installments, we’ll follow Mike’s continuing battles about SAT testing, especially more recently in California 5 with this understanding about the personal genesis of such views.

Early Influences: A Second Big Turning Point

Nancy Mancini, Stanford’s interviewer for the John W. Gardner Legacy Oral History Project, asks a key question that pivots us to a second turning point in Mike’s early years. Let’s listen in:

Clip 4: “Did you play all four years?”

Mike concludes with a chuckle that his “football knee” is “my only physical ailment.”

Mike Kirst’s year-book picture as a freshman at Dartmouth in 1956. Photo courtesy of Dartmouth University and Mike Kirst.

Replying to Mancini’s next question, “How did…not being able to play football anymore change your experience [at Dartmouth]?” We hear why this was in Mike’s words “a turning point” when he explains: “It gave me a lot more time to focus on academics. I became more interested in academics than sports… I think I took nearly every economics course they had in the department at Dartmouth.”

Mike elaborates on this “turning point” characterization in his entry to the Dartmouth yearbook, “The Paths We Have Taken,” published in 2011, a half-century after his graduation:

“Dartmouth was a time of great transformation for me and built the academic base that I have used all my life…. [T]here was something about the teaching and subject matter at Dartmouth that catapulted me to a career in research, teaching, and public policy”…despite [being] accepted from the waitlist and not having the strongest academic preparation of our entering class.…” Adding later in that entry: “Dartmouth…built into me a zeal for…discovery and contemplation.” 6

Mike also notes in this 50-year anniversary yearbook, another attribute he picked up at Dartmouth, from his days in the Theta Delta Chi fraternity: his predilection for a “work-hard/play-hard pattern” which “lasted until I was in my late 20s.” He emphasizes the “play-hard” part of his Dartmouth years, reminiscing in his anniversary yearbook entry about “the amazing parties, road trips, and legendary Dartmouth characters” whom he felt were brought back to life in the movie Animal House, ending his entry noting that “I have watched several times” since.

We’ll explore both sides of the work-hard/play-hard dichotomy more in future installments of this series as well as some later influences in his personal and professional development to portray more fully the personal side of this often behind-the-scenes reformer.

Early Influences: A Third Big Turning Point

In his 2014 recording for Stanford’s “Autobiographical Reflections” series, Mike makes a brief mention of a third early turning point—during the summer of his junior year at Dartmouth. Let’s listen in:

Clip 5: The College Summer Job When Mike Became “Hooked On Washington”

Let’s listen to talk about his first stint in D.C.:

I asked Mike recently for the name of the professor who led Mike to the summer internship and got him “hooked on Washington.”

“Martin Segal, Professor of Economics at Dartmouth,” he replied.

The “down there” reference in Mike’s mention of this D.C. internship was the legislative relations office for the U.S. Department of Labor, in 1960, the last year of the Eisenhower administration with a Democratically controlled Congress. Mike observed that the experience was “really interesting” and “very rewarding” and that it provided him “a good view of federal civil service and the high quality of people that were in it.”

Mike also revealed that “I used the head of the unit there for legislative analysis for one of my letters of reference for graduate school” and that this internship was influential in his choosing the school of public policy for his initial area of concentration for his master’s and doctoral studies at Harvard.

And what Dr. Segal did for Mike—plugging him into a vast network of contacts, leading to a pivotal opportunity as a graduate student—turns out to be one of Mike’s distinguishing M.O.’s throughout his career as well and remains a timeless legacy.

“Early Influences”: A Final Note for This and a Tee-Up for the Next Installment

We heard Mike mention in recordings that his father’s business and his family circumstance originally narrowed his college aspirations and explorations. However, we should also note Mike’s comment in his 2018 Stanford oral history interview that “[i]t was a really nice era. People born in 1939 were really blessed because [they got to experience the post-war period].”

Throughout his career, we’ll see that Mike continued to put the plight of those coming from economically disadvantaged neighborhoods at the center of his reform concerns and efforts while maintaining a rather optimistic or at least matter-of-fact personal perspective. While his preference to work behind the scenes would seem to embody the general moniker of the “Silent Generation,” Mike’s more buoyant characterizations of the era in which he grew up as “really nice” and “the Fabulous Fifties” correspond more closely to the title of Elwood Carlson and Charles Nam’s sociological study of this time, The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. 7

Mike Kirst comes to Washington at the age of 25, meeting and serving as an adviser for President Lyndon Johnson at the inception of Title I, ESEA

We’ll hear then in the next installment Mike reflect on his transition to and doctoral studies at Harvard, including receiving some bad advice from his college advisers but also making a key—and, as it turns out, long-term and multifaceted—connection with John W. Gardner, president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, known as “one of the most powerful behind-the-scenes figures in education.”8 Installment Seven will also document how a very young Mike first met President Lyndon B. Johnson and served, like his mentor Mr. Gardner, as a behind-the-scenes adviser at the inception of still today the largest federal education program which the President pushed through Congress in 1965—the historic Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA)—as well as helped introduce the President to the woman and wrote his best-selling biography.9

Stay tuned to hear more about these and other early Mike Kirst influences, relationships, stories, and accomplishments.

Editor’s Note: The Appendix for “Conversations With and About Mike” contains transcripts for the recorded audio and video clips. To view the Audio Transcripts go to this page >

Footnotes

- Chaisson, D. (September 27, 2019). “Readers, I Googled It.” The New Yorker: www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/02/reader-i-googled-it

- The two autobiographical recordings Mike conducted for Stanford University used for this installment are:

A. Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

B. Mike Kirst interview with Nancy Mancini, May 3, 2018, for the John W. Gardner Legacy Oral History Project (SC1355). Department of Special Collections & University Archives, Stanford Libraries, Stanford, Calif. https://purl.stanford.edu/fb149yr2480 - See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silent_Generation

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Blackman

- See for example https://edsource.org/2017/turf-battle-developing-over-who-can-test-californias-11th-graders/578262 and https:// edsource.org/2018/substituting-sat-act-for-the-smarter-balanced test-is-not-a-smart-idea/601775

- Paths We’ve Taken, Dartmouth 1961 Reunion Book. (2011). p. 207.

- Carlson, E., (2008). The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom.

- As cited in https://historicalsociety.stanford.edu/discover-history/oral-history/projects/john-w-gardner-legacy-oral-history-project

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doris_Kearns_Goodwin