18th Installment: Mike on the International Stage

"Conversations With and About Mike"

Mike Kirst’s first publication on education outside the United States, drawing on the work of an invited international delegation which he led.

“One of the things that is so fascinating about academic research is how personal it is.”

Malcolm Gladwell, in Psychology and the Real World1

Author and influential thinker Malcolm Gladwell speaks to us all in this observation, but especially to me as the biographer behind the depiction of Mike’s life history as told in Mike Kirst: An Uncommon Academic.

Mike’s International ‘Revelatory Arc’: An Overview

This current installment, “Mike on the International Stage,” is one of three final segments for the upcoming more traditional book version of this biography project. Accordingly, they will be more reflective, commenting more directly on Mike the person, and the traits that help us understand him as not only an academic but also as a person.

Especially Mike’s achievements in his eight years serving for the second time as the President of the California State Board of Education (2011-2019), many of which are documented in the previous installment, have received rather wide coverage and attention. In contrast, Mike’s academic work on the international stage, spanning more than four decades thus far, has received scant attention, but may even be more important in helping us understand him as a person, his core values, and some of his most endearing and enduring traits.

The “Mike on the International State Chronology” table below summarizes this rather uncharted aspect of Mike’s research with an important purpose: As Gladwell notes, while university-based academics are “required to handle what comes at the door, the “careers of academic scientists very quickly become particularized and idiosyncratic.” He concludes that “one of the things that is so fascinating about leading academics is that they “often have the freedom to pursue things that interest them, and as a result, their career arcs become fundamentally revelatory.”(emphasis added)2

The entries in the chart below, accordingly, illustrate this “revelatory arc” for Mike; they span the years from 1978, when Mike was 39-years old to now as he serves as a “Senior Fellow in Residence,” now in his 80’s, at the Learning Policy Institute (LPI).

We’ll find in this installment how these three identifiable, inter-related stages below in this arc are “revelatory” in several ways:

- Stage I: ‘Dabbling,’ then Developing a ‘Zest’ for International Perspectives (1970s and ’80s)

- Stage II: Becoming a Voice on International Education Comparisons (1990s)

- Stage III: Examining Systemic Reform Exemplars Abroad (Current).

We start at the end of this arc for a first glimpse.

A View from the Current Phase of the International ‘Arc’

Mike recently offered us a peek into how his international work over the years has helped shape his fundamental beliefs about what is needed for education reforms that work and stick in this country.

Photo excerpted from Education Commission of the States (ECS) website.

The occasion was his acceptance in the fall of 2021 of the James Bryant Conant Award bestowed on him by the Education Commission of the States (ECS), citing him “for his unwavering commitment to improving school finance systems to serve students more equitably.”3

ECS elaborated in its announcement of the award, “[p]erhaps most notable” of Mike’s achievements “is the development of California’s Local Control Funding Formula…enacted in 2013”–a reform package that “upended the state’s previous way of funding schools to more equitably distribute funding to the schools with the greatest needs…[by] eliminating more than 40 categorical programs, giving more flexibility to districts to respond to local challenges and opportunity.”4

As we heard in the previous installment and as noted by ECS, “Kirst is credited for not only developing the formula but also creating and guiding the strategy and political coalitions needed to ultimately make the formula a reality.” And quoting a former state superintendent, the announcement called this package of education reforms “likely the largest school equity restructuring ever undertaken in the state or the nation.”5

Mike’s acceptance remarks touch on several aspects of his work, and he concludes with lessons about exemplars forthcoming from this current stage of his international arc:

Media 1 (Video): Mike Kirst: “As we move into the future, I’m looking at other countries…that did large-scale (standard’s based) reforms… ‘statewide'” (2 minutes, 30 seconds)6

When accepting this award, Mike relies as he so often does on a sports analogy to note that the “California Way” reforms are only”in the fourth inning of a nine-inning baseball game [delayed due to being] rained out by Covid.” He speaks of what he sees as the most productive way forward to advance those reforms, “capacity building” and entices us with the promise of exemplars for moving forward, as gleaned from international research and documentation of the work of a few leading states.

He cautions that “states… can’t mandate, regulate…. or even incentivize very well what teachers and principals and school people do together.” So, when receiving this lifetime achievement award, he informs state policymakers in the U.S. that the way to move ahead after the pandemic may lie in the research he’s currently undertaking in other countries–namely in Western Australia, Ontario Canada, and Singapore, as well as a state or two in the U.S, which have undertaken “capacity-building” on large-scale that they “build… into the districts … through the professional work of the teachers strengthened by expanded professional development.”

He offers this tantalizing heads-up: “I can’t describe all of this to you now. But you’ll be hearing more from me about all this…in the next months and years.”

We’ll know more about “all of this” when Mike completes a monograph he has been working as a Senior Fellow in Residence with his colleagues at the Learning Policy Institute7. For now, though, let’s look back to the starting point on Mike’s international arc, more than four decades ago–in a China that was quite different from today.

Mike on the International Stage Chronology*

Stage I: Developing a "‘Zest’ for International Perspectives" (1970s-1980s) | |

1978 | Article: “Reflections on Education in China,” Phi Delta Kappan |

1981 | Article: “Japanese Education: Implications for Economic Competition,” Phi Delta Kappan June, pp. 707-708 |

1981-84 | Editorial board: American Journal of Education |

1982-85 | Editorial board: Phi Delta Kappan |

1983 | Monograph: A Perspective on Education in Hong Kong (Government of Hong Kong, 1983, with John Llewellyn, et al.) |

1983 | Book: Contemporary Issues in Education: Perspectives from Australia and U.S.A. (Berkeley: McCutchan,), with Greg Hancock and David Grossman |

1984 | Article: “The Political Economy of Education in Hong Kong,” The Chinese University Education Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1 (June 1984), with Ming K. Chan |

1986 | Article: “Hong Kong: The Political Economy of Education,” in Frederick Wirt (ed.), Education, Recession and the World Village (Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis, Inc.), with Ming Chan |

Stage II: Becoming a Voice on International Education Comparisons (1990s) | |

1990s | Visiting Professor: Stanford at Oxford, England and Visiting Professor, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary |

1991 | Article: “The Need to Broaden Our Perspective Concerning America’s Educational Attainment,” Phi Delta Kappan |

1993 | Article: “Strengths Weaknesses of American Education,” Phi Delta Kappan, pp. 613-618 |

1993-98 | Position: Chairman, Board of International Comparative Studies in Education, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

1997-Present | Position: Member, International Academy of Education |

2000 | Article: “Bridging Education Research and Education Policymaking,” Oxford Education Review 26(4) |

International-Focus Dormant (2000-2020)

Stage III: Examining Systemic Reform Exemplars Abroad (Current) | |

2020-Current | Draft monograph in process, examining standards-based systemic reform efforts in parts of Australia, Canada, Singapore, and U.S., Learning Policy Institute |

*Derived from Mike Kirst’s Resume

The ‘Arc’ Began with “Dabbling”

“I began to get this zest for international perspectives… That was the beginning of trying to get outside the box of the U.S. in my thinking.”7

Mike Kirst

During Mike’s first years as President of California’s State Board of Education, the state was experiencing the start of a major tax revolt as an even larger ideological revolt was unfolding in China. This led to China offering Mike and some of his colleagues a chance to apply for a group visit to its country which he did and which the Chinese government accepted. The California delegation, under Mike’s leadership, began with a nearly three-week guided official tour of its schools, universities, government facilities, homes, factories, and cultural attractions in select cities, including Beijing (then more commonly called “Peking”) and Shanghai as well as some rural areas. Mike very much enjoys telling this story. Let’s listen in:

Media 2 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “We applied as the California State Board of Education. And they accepted us. And they asked me to bring, in addition, deans of engineering (and) science educators. (1 minute, 22 seconds)8

Susan Shirk, China scholar, later to become a U.S. Secretary of State for China. Photo from the University of California, San Diego archives.

You can hear Mike’s enthusiasm about this visit in his voice and certainly his enjoyment in telling about this being an initial visit of Susan Shirk, who at the time was an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department at the University of California, San Diego–a scholar on China who could never visit there–and who later was to become the U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State responsible for China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Mongolia and for the East Asia and Pacific Bureau at the Department of State under President Clinton from 1997 to 2000.9

Mike’s first “international” publication in 1978 reflected on this visit. Some of these observations tell us almost as much about Mike as it does about what this U.S. delegation learned from China and ostensibly what China might have learned from the California scientific and engineering academics who the Chinese requested be in the delegation.

The report’s central finding was that China’s “leading educational issue” at that time was “the tension between equality and merit” — a theme highly congruent with Mike’s ruminations early in his career dealing with ESEA, Title I and a focal thrust of the “California Way” funding formula for which many consider him to be “the father.”10

In China, Mike found a “trade-off between equality and efficiency in education, [with] the people advocating technical and scientific efficiency clearly in the power positions.” Nonetheless, he found nine specific examples of what he characterized as “drastic changes taking place” in new attitudes that “favored merit over equality.”

(You can find the full text of this 1978 Phi Delta Kappan article as well as the one below on Japan in the “Resource” section of the website for the Mike Kirst Biography Project along with several other published articles based on his international experiences…all of which are otherwise basically inaccessible to the general public.)

Photo from 1981 Phi Delta Kappan.

Early in the 1980s, the Japanese Ministry of Education invited Mike to visit the country to help them address their concern at the time “that academic competition is so intense that Japanese children are neglecting other aspects of their development.”11

Mike produced a think piece, published in the summer of 1981 in Phi Delta Kappan, reflecting on what American educational policymakers could learn from Japan, similar to what we heard Mike promise from his current work as the Senior Fellow in Residence for the Learning Policy Institute.

In the 1981 Phi Delta Kappan article, Mike observed that “[t]he Japanese are setting standards of scientific literacy for their entire school population, and that they are developing an intensive science and math track for their ablest students.” He notes, however, that “while Japanese schools are better equipped than their U.S. counterparts to prepare workers for the future,” “Japan’s success [in this area] has been purchased at a high price” especially in its inequities and in its then “persistent … teaching strategy … of imitation and rote learning.”12

In addition to his China and Japan travel in the 1980s, he also visited several European countries for the first time in his life (Spain, Italy, France, and Germany) at the invitation of education policy colleagues and fellow Stanford professors, noting recently that “it was really something I wanted to do to expand my horizons” and then adding “I got all these free trips” which he was sometimes able to do with his wife, Wendy.13

One such example was a two-week Voice of America program trip to Europe which Chester Finn had invited him to join. Mike explained later “that was part of an era” of international experiences during which “I really talked and interacted with lots of people in lots of settings…and that was fabulous fun.”14

During this period he accepted invitations to join the editorial boards of two important education journals, The American Journal of Education and Phi Delta Kappan, offering him additional publication venues as well as expanding his network of policy researchers.

The U.S.-Australia Education Policy Project: 1980s

From “Dabbling In” to a “Zest For” an International Perspective

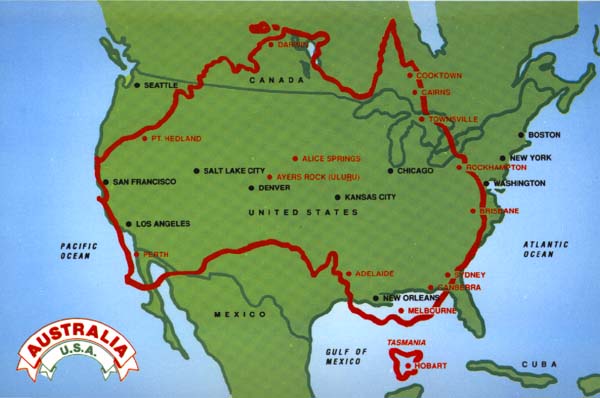

Australia’s map outline is superimposed upon a map of the United States. Image from The Australian Government.

In the early 1980s, Mike’s interest in international comparisons deepened; and his friend and colleague Jim Kelly at the Ford Foundation provided the seed money for a comparative study of education policy in the United States and Australia.

Let’s listen in as Mike explains this transition from “dabbling” to “developing a zest”:

Media 3 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “Australia was a great place to start because….it has state governments and they’re so powerful ….(51 seconds)15

The 1983 book, Contemporary Issues in Education: Perspectives from Australia and U.S.A. (which Mike co-edited with Greg Hancock and David Grossman) resulted from this research.

The Ford Foundation had organized “a bilateral conversation on education policy issues” in February 1977 for U.S. and Australia representatives to discuss “four topics of mutual interest — inter-governmental relations in education; the school-work interface; choice and diversity in education; and the role of the teaching profession in decision making.” Both countries had begun major federal education initiatives in the prior decade: “[t]he United States Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was partially replicated by the passage of massive Australia initiative in 1972” through the Disadvantaged Schools Program of Australia.16 Both the U.S. and Australian programs provided federal funds to schools operated and funded primarily at the state level and both were intended to improve schools in areas with high concentrations of poverty. However, they differed in how they targeted funds, regulated educators’ uses of the funds and allowed granted decision-making to local and state educators.

The U.S.’s federal research arm, the National Institute of Education (NIE) and the Ford Foundation, funded research to explicate the issues the programs faced as well as their similarities and differences.

So, these programmatic, governance, funding, and cultural, similarities and differences between the U.S. and Australia at the time–as well as geographic size–provided an almost ideal “ground zero” for Mike’s “trying to get outside the box of the U.S. in (his)thinking.”

In this commentary, Mike mentions that the U.S./Australia Education Policy Project represents for him “the start” or the spark for his more serious engagement in international work; however that international spark almost simultaneously ignited in another even more remote setting abroad: Hong Kong.

OECD’s Review of Hong Kong Education: 1980s

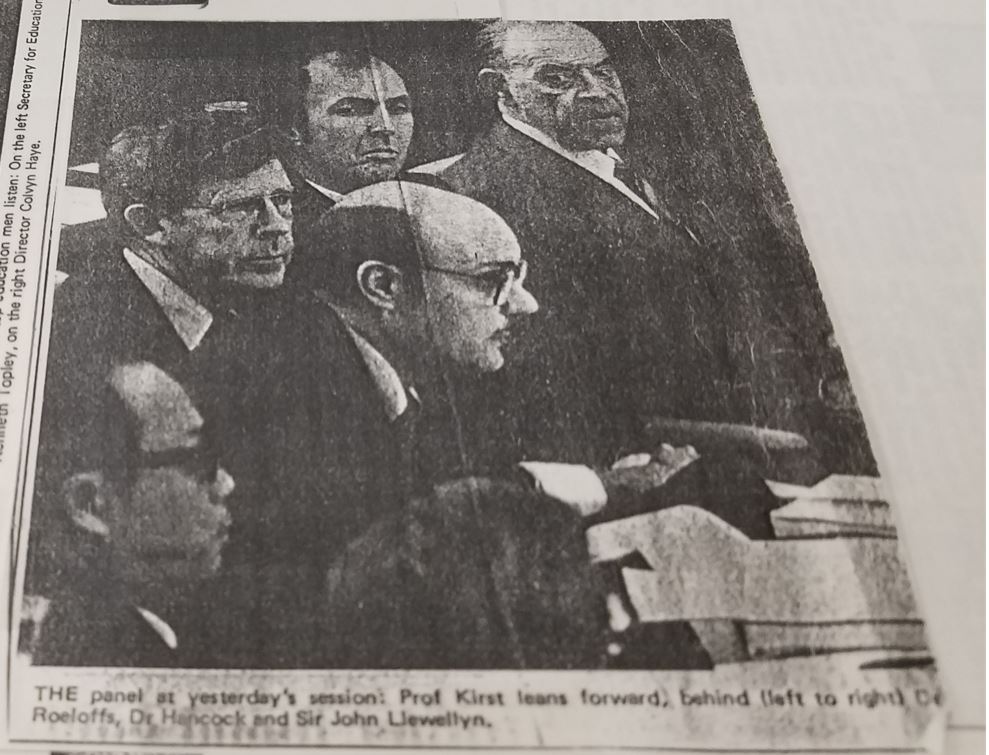

Mike, flanked by fellow members of an OECD review panel. Photo from the Hong Kong Standard, March 30, 1982, archived at the Hoover Institute.

Two entries in Mike’s resume beg for elaboration:

- “A Perspective on Education in Hong Kong (Government of Hong Kong, 1983, with John Llewellyn, et al.),”

- “The Political Economy of Education in Hong Kong,” The Chinese University Education Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1 (June 1984), with Ming K. Chan”

In 1843, Hong Kong had become a British colony, its official designation being “British Hong Kong,” which held until the British Nationality Act of 1981 officially changed Hong Kong to a “dependent territory” of Britain, effective January 1983. Initially, the renaming did not change how the Hong Kong government operated; however, it did affect the nationality status of its then 5 million inhabitants, which, in effect, meant that nationality status would no longer automatically be transmitted to the descendants of its citizens. (And in 50 years Hong Kong would be transferred to China, as required by the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984.)

Slightly in advance of Hong Kong’s change from being a colony to being a “dependent territory,” the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) of the United Nations convened a panel of experts to document the status of education in Hong Kong. Panel members were His Excellency, the Governor, Sir Crawford Murray MacLehose, as the honorary chair; Sir John Llewellyn (the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Exeter, from the United Kingdom), chair of the Panel of Visitors; Dr. Greg Hancock (from Australia), Rapporteur; Professor Michael Kirst (from the U.S.), Member; and, Dr. Karl Roeloffs (from Germany and a Stanford graduate), Member. The members of the committee are pictured above huddled around Mike, in the Hong Kong Standard’s March 30, 1982 press coverage of the Panel’s presentation of its findings and recommendations.

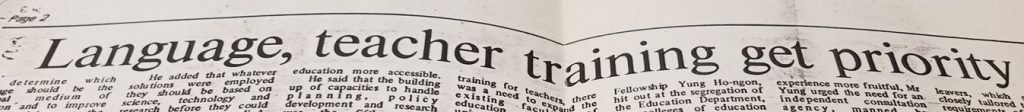

The press focused part of its coverage on the then politically charged issue, the role of native-language instruction in Hong Kong’s public schools (an issue familiar to Mike from his work in California). The Hong Kong Standard reported that as a first priority “[t}he international panel conducting a review of the Hongkong education system, yesterday urged a shift toward universal use of the mother tongue in the early years of education” — more specifically, starting in kindergarten. The Australian member of the panel, Dr. Greg Hancock, then the Chief Education Officer at the Australian Capital Territory Schools, whom Mike had met through the U.S./Australia Project, further noted that the Hong Kong system “could afford to reduce the emphasis on English in secondary education as well.”

A second and related policy area the panel identified was what Mike now calls “capacity-building.” The lead OECD representative, Dr. John Papadopoulos, put it this way: “To determine which language should be the principal medium of instruction and to improve teachers’ training are to be the two priorities.”

Mike commented on funding levels as well. He emphasized, with his Title I and related California policy background, that it’s “ironical that the low standards schools receive a lower subsidy from the government”; he advocated that the emphasis on financing schools should be on “how to level up the weakest schools without dragging down the good schools,” an issue he and other California policymakers had faced, especially after the K-12 funding constraints required by the passage of Proposition 13.

We delve into the background and findings of this group for insights into Mike’s international work but also because the documents, themselves, are not easily accessed. When I could not locate them online or elsewhere, I asked Mike about them, which prompted him to recall vaguely that because of potential international security concerns about this work in then a British protectorate in a communist country, the Hoover Institute on War, Revolution, and Peace at Stanford had requested that he turn over his archives and any related pertinent materials he had from this work.

In September of 2018, staff at the Hoover Institute located and shared with me three boxes marked “Kirst.” Staff supervised my work there at the Institute and allowed me to take pictures and notes. This summary is from the March 1982 “Restricted Draft” of what was to become the final report of the invited OECD’s Panel of Visitors, “A Perspective on Education in Hong Kong, 1982.” The document itself remains intact in the Hoover Institution at Stanford.

Title page for the 1982 report of the OECD’s Panel of Visitors. Photo from the Hoover Institute’s archives.

Front-page headline of OECD report in Hong Kong Standard, March 30, 1982. Photo from Hoover Institute’s archives.

Second-page headline of OECD report in Hong Kong Standard, March 30, 1982. Photo from Hoover Institute’s archives.

Let’s listen to Mike’s story of his challenge to the Hong Kong leadership, particularly, “His Excellency, the Governor” (Sir Crawford Murray MacLehose), on being “outrageously culpable” in not investing in training and education beyond high school for its citizens.

Media 4 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “I was the one that was the most obstreperous of the group”…about the British government being “outrageously culpable” in not investing advanced training and education “and not worrying about quality” of Hong Kong teachers and in general in post-secondary education opportunities for its citizens. (1 minute, 23 seconds)17

Becoming a Voice on International Comparison

After his Australia and Hong Kong experiences in the 1980s, Mike’s travels continued to several European countries in the early 1990s. Beyond these trips, he also served as a Visiting Professor for the Stanford program in Oxford England, and at the Central European University in Budapest, Hungary.

That Mike had begun to become a voice on the topic of international comparisons was already apparent when he was called upon as a national expert to testify before the first meeting of the National Education Goals Panel in 1990.

Mike used his closing minutes before this national panel of education policymakers to urge these leaders and their staff to do more than a little digging when reading news reports about how far behind U.S. students are compared to their counterparts in other countries. Let’s listen in:

Media 5 (Video): “Every time I pick up a paper, I see that we’re ranked twelfth or eleventh. You need to understand in detail how international assessments are put together and who is doing it” (1 minute, 4 seconds)18

C-SPAN October 10, 1990 source video URL: https://www.c-span.org/video/?14434-1/national-education-goals

Again, Mike turns to a sports metaphor–this time to the international Olympics–advising these leaders that they should “look carefully at … these international comparisons” and ask themselves if the things being compared are “the appropriate things the American system should shoot for.”

In the subsequent year, 1991, Mike wrote a piece for Phi Delta Kappan (PDK) entitled, “The Need to Broaden Our Perspective Concerning American’s Educational Attainment.” A little over a year later, this same education journal published a second piece of Mike’s on international education comparison, “Strengths and Weaknesses of American Education.”

Mike returns to the international education Olympics metaphor in the 1991 article by centering the piece on the question: “Why does the international education Olympics end at age 17?” He basically argues that “if we are to rely so heavily on international education comparisons….then the comparisons should include all levels of the education system.”(emphasis added).19

Mike centers the second PDK article, published in 1993 on a related but broader international comparison of the U.S. education system: “Are we good enough to stand up to worldwide competition?” His response to this question is that “we need to build upon our strengths and shore up our weaknesses.” On the strengths side, Mike raises the question with a rather California-biased answer for him: “Is there a better technical university in Japan or Germany than MIT, Cal Tech, or Stanford?” On the weaknesses side, Mike returns to his emphasis we heard in earlier installments that at least part of the problem in America is overall “lack of support here for children, compared to other nations in the industrialized world.”20 Not just in schooling but in broader areas such as the increasing incidence in the U.S. of children living in poverty, having insufficient health care, and basic safety protections.

Mike Chairs Board Responsible for International Education Comparisons at Key Moment (Mid-to-Late 1990s)

Edited by James Guthrie and Jane Hansen. Photo from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.

In a recent interview about his international work, especially this OECD review in Hong Kong, Mike noted, “you can see the international strands building and building.”21 He emphasized that the important culmination of this international involvement was his role for five years in the 1990s as the Chair of the Board of International Comparative Studies in Education (BICSE) for the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) from 1993-1998, a pivotal time in this board’s history.

For almost half a century, UNESCO had been the leading source of statistical information on education systems around the world in the nearly 200 countries in its membership but had found itself “facing increasing demands for improved statistical products and services….as the world’s hunger grows for information about education systems, how they work, and what they accomplish.”22

So, in the fall 0f 1994, UNESCO’s Division of Statistics asked BICSE to study this matter as a key step in establishing a strategic plan “for the improvement of the quality, comparability, and relevance” of the organization’s education data collection systems. And the NAS leadership asked Mike to serve as the Chairman of BICSE during this critical time.

Photo from the National Academic of Sciences website.

Mike as BICSE Chair cites the work of Janet Jansen, the Division’s staff director, and his longtime colleague, Jim Guthrie (at that time heading the Peabody Education Policy Center at Vanderbilt) for the writing and editing of this seminal 1995 report to UNESCO.

The report begins, “Early in its review BICSE realized that it would be insufficient to recommend marginal changes to UNESCO’s data collection and reporting program and practices.” The study “revealed more fundamental concerns” about the “confidence in the quality” of UNESCO’s data after “[t]en years of retrenchment in the wake of serious budgetary pressures” which had “seriously damaged the division (the Division of Statistics).”23

The report issued two striking recommendations, the first to strengthen the mission of the statistics branch and the second to increase the division’s autonomy, more specifically articulating these two priorities:

- “Mission: UNESCO should articulate and legitimate a broader mission for its statistics branch.”

- “Organizational Structure: The Division of Statistics should be granted functional autonomy within UNESCO.”24

In the years following the publication of this report, BICSE spent considerable time and effort overseeing the development and start-up of what it considered to be a better test for international comparisons, originally called “The Third International Mathematics and Science Study” (TIMMS). While keeping the same “TIMMS” acronym, as the test continued to be refined and expanded over the years, its name accordingly changed into the broader “Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study” administered by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

This TIMMS test has been administered every four years since 1995. As Mike recalls, the U.S. needed “to provide the leadership to initiate it.” So it was important for them to have a leading voice in American education as the Chair of BICSE. Mike also recalls “many long technical sessions to approve the curriculum coverage and other technical issues of TIMMS” at the time headquartered in Amsterdam, but more recently moved to Boston College.25

In 2000, the OECD started its own large-scale international study and test, the “Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)”. While both TIMMS and PISA were designed to compare educational achievement across countries, the two tests target different schools and pupils and differ in other important ways. TIMMS is more curriculum-based while PISA puts more of an emphasis on assessing “the application of skills to real life.”26 Most importantly for Mike, who prefers TIMMS over PISA, is that TIMMS focuses on what is actually taught; whereas, PISA emphasizes what should be taught. (For a more complete comparison of TIMMS and PISA see, for example, “How Similar are PISA and TIMMs Studies”).

The debate continues among academics, policymakers, and various pundits about the merits, relevance, and other considerations in using these and other tests purporting to compare the achievement of K-12 students in American schools to those in other countries across the globe. For example, Mike is continually debating the merits of the two tests and their influences on educational policymakers with Eric (Rick) Hanushek, a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and Tom Loveless, a former Senior Fellow at the Brown Center on Education Policy at the Brookings Institution.

Tom Loveless, former Resident Education Scholar at the Brookings Institution. Photo from Educators Writers Association.

Here is a sampler of these exchanges: Mike recently inquired of Tom Loveless, “Why does PISA receive so much more publicity than TIMMS?” receiving from Tom, “I agree about PISA overshadowing TIMMS” and speculating that OECD, PISA’s sponsor is fairly skilled at describing the results and implications. Loveless also notes that PISA is perceived as a more European-centric test, and the ministries of EU countries gobbled it up. He feels the TIMMS people are “more scientific but less politically savvy.”26

Eric (Rick) Hanushek, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. Photo from the Hoover Institution website.

On the other hand, Hanushek, responding to a similar inquiry from Mike observes simply, “I know that there is a line of discussion about whether the TIMMS tests are better than PISA. I have not taken that very seriously. They are highly correlated with each other.” In addition, “Scores cannot be directly compared because they are calibrated to a different set of countries. The TIMMS scores say that we do better than a group of developing countries. We don’t think they say anything different than the PISA scores. We definitely have a problem.”

Mike, the consensus-seeking academic, in an email to Hanushek concedes, “I agree we have a problem and will argue we should try harder and not give up.”27

A Final Reflection

We return to Mike’s comments as he accepted the 2021 ECS award as he tells the state education leaders that he’s looking to other countries for ways to continue the “California Way” package of reforms. He notes, “I look forward to working with ECS on refining the reform package, tailoring it to states, and working with all of you to make a better future for education.”

Mike Kirst’s long-time colleague, Mike Usdan, speaking more broadly about what makes Mike “an uncommon academic,” offers up this insight about Mike that certainly applies to his ongoing California and national reform work… and now his curiosity in seeking out international insights for his ongoing and future research.

Media 6 (Audio): Mike Usdan: Mike has “an incredible mind…with an intellectual curiosity that’s insatiable.” (30 seconds)28

Stay tuned for the next installment to hear more about how the “insatiable curiosity” Mike Usdan highlights in this clip continues even into Mike’s octogenarian years.

Editor’s Note: The Appendix for “Conversations With and About Mike” contains transcripts for the recorded audio and video clips. To view the Audio Transcripts go to this page >

Footnotes

- Gladwell, M. (2015). In the “Forward” to Gernsbacher, & Pomerantz, M. (Editor), Psychology and the Real World. Worth Publishers (Secon Edition), p. ix.

- Gladwell, M. (2015). In the “Forward” to Gernsbacher, & Pomerantz, M. Editors. Psychology and the Real World. Worth Publishers, (Second Edition), p. ix.

- This annual honor recognizes “individuals whose efforts and service have created a pronounced and lasting influence on American education and have demonstrated a commitment to improving education across the country in significant ways.” Previous recipients have included Ted Sizer; Mike’s long-time colleague, Linda Darling-Hammond; as well as his mentor and neighbor on the Stanford campus, John W. Gardner.

- Education Commission of the States. (July 8, 2021). Website announcement. Congratulations to Michael Kirst, 2021 Recipient of the James Bryant Conant Award.

- Education Commission of the States. (July 8, 202). Website announcement. Congratulations to Michael Kirst, 2021 Recipient of the James Bryant Conant Award.

- Excerpted from 2021 Education Commission of the States Video: https://vimeo.com/595758707

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, February 23, 2022.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, August 23, 2021

- Susan Shirk’s curriculum vita: https://gps.ucsd.edu/_files/faculty/cv-only/shirk_cv.pdf

- See: https://edsource.org/2013/michael-kirst-father-of-new-school funding-formula-looks-back-and-at-the-work-ahead/33408

- Kirst, M. W. (October 1978). Reflections on Education in China. Phi Delta Kappan. Vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 124-125.

- 12 Kirst, M.W. (June 1981). Japanese Education Its Implications For Economic Competition in the 1980s Phi Delta Kappan. Vol. 62, No. 1, pp. 707-708.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, May 11, 2022.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, May 11, 2022.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, August 23, 2021.

- Kirst M., Hancock, G., Grossman, D. (1983). Contemporary Issues in Education: Perspectives from Australia and U.S.A. Berkeley, CA: McCutchan, pp. 9-10.

- Mike Kirst interview with author, May 11, 2022.

- Excerpted from 2017 C-SPAN October 10, 1990. video: https://www.c-span.org/video/?14434-1/national-education-goals

- Kirst, M.W. (October 1991). The Need to Broaden Our Perspective Concerning America’s Educational Attainment. Phi Delta Kappan. Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 118-120.

- Kirst, M.W. (April 1993). Strengths and Weaknesses of American Education. Phil Delta Kappan. Vol. 74, No. 8, pp. 613-616, 618.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, May 11, 2022.

- National Research Council. (1995). Executive Summary: Worldwide Education Statistics: Enhancing UNESCO’s Role. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. National Research Council. (1995). Executive Summary: Worldwide Education Statistics: Enhancing UNESCO’s Role. Washington, DC:

The National Academies Press. - National Research Council. (1995). Executive Summary: Worldwide Education Statistics: Enhancing UNESCO’s Role. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- National Research Council. (1995). Executive Summary: Worldwide Education Statistics: Enhancing UNESCO’s Role. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. The Third International

- Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMS). For example, see https://issbd.org/resources/files/newsletter_198.pdf and email correspondence from Mike Kirst, April 19, 2022.

- Email correspondence from Mike Kirst, April 20, 2022.

- Email correspondence from Mike Kirst to Rick Hanushek, April 21,22.

- Mike Usdan interview with the author, September 14, 2018.