16th Installment: Mike’s ‘Interregnum Years’: Part II: 2000-2010

"Conversations With and About Mike"

Slide from John Fensterwald’s (EdSource’s Editor-at-Large), June 2021, presentation on California’s school finance system quoting an issue brief Mike co-authored in 2008. Courtesy of EdSource.

In the previous installment, we noted that the 28-year period–1982 to 2010–might be considered as “Mike’s Interregnum Years.” Relying on the Oxford Languages definition of “interregnum” as “an interval or pause between two periods of office” derived from the same Latin word meaning “an interval between two reigns,” the two “reigns” in this case being Jerry Brown’s two times in office as Governor of California.1 That installment also noted that these ‘interregnum years’ for Mike were among some of his most prolific professionally, leading us to split the period in two: the previous installment chronicled how Mike’s focus and influence grew in K-12 education during roughly the first two decades of the period–from 1982 to 2000.

This installment covers the second part of the interregnum years as Mike worked with Jerry Brown, not as governor but as the Mayor of Oakland (from 1999 to 2007), and their important discoveries. During that time Mike was also expanding his academic interests, pursuits, writing, and influence in what he calls his “K-16” years. At this time, Mike retired from Stanford’s faculty after 37 years, becoming, at the age of 67, a very active professor emeritus who–then as now–maintained his university office in Room 121 of Cubberly Hall on the Stanford campus.

Advising Jerry Brown as Mayor of Oakland (1999-2007)

“The best thing that happened for both of us was for him [Brown] to be Mayor of Oakland” Mike Kirst in his 2014 Autobiographic Reflections2

Even before completing his first set of terms as California’s governor (1975-1981), Jerry Brown made his second unsuccessful run for the U.S. presidency in 1980. In 1982, Brown lost his U.S. Senate race to Pete Wilson, who was then mayor of San Diego. After a few years, Brown moved to Japan for several months in late 1986 and early 1987 to write a book and study Zen Buddhism.

When he returned to the states, he mounted a third unsuccessful bid for U.S. President and moved from San Francisco to the Jack London District of Oakland, a predominantly minority city of 400,000. There he built a multi-purpose complex, where he both lived and worked, and launched a national talk radio show from its broadcast studio. The talk show ran through October 1997. When Oakland’s mayor, Elihu Harris, chose not to seek re-election, Brown ran in the city’s 1998 mayoral election as an independent and won with a whopping 59 percent of the vote in a field of nine other candidates. His major campaign promise was to fix Oakland schools.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1982, Mike led the charge to found the multi-university think tank Policy Analysis for California Education (PACE, see the previous installment for details). He also enhanced Stanford’s role in a second university-based research group, the Consortium for Policy Research in Education (CPRE), (described, as well, in Installment 15).

Oakland, January 4, 1999, Jerry Brown waits to deliver a speech at City Hall following his swearing-in. UPI photo

Soon after being elected Mayor, Brown established the Oakland Mayor’s Commission on Education, which included Mike, to guide him in making good on his promise to fix the schools. Soon, however, “bureaucratic battles” thwarted his efforts. Brown later, after completing at the end of his two terms as mayor of Oakland, conceded that he never had control of the schools and that his education reform efforts were “largely a bust.”4 Mike was later to call this “the learning period we had together.” Let’s listen in:

Clip 1 (Audio): Mike Kirst: We both “began to dig directly into how you improve instruction…and with that was learned the lesson of ‘humility.’” (Stanford Emeriti Council presentation, (1 minute, 33 seconds)5

Jerry Brown with students at Oakland Military Institute. Photo from the school’s website.

Mike explains in this 2014 Autobiographical Reflections recording for Stanford, approximately a decade later, that this attempt for a mayoral takeover of the Oakland public schools had been a failure and even then was ambivalent about the effectiveness of Brown’s two charter schools (the Oakland School for the Arts and the Oakland Military Institute.)6 Brown defended his support for the military charter school to a KQED reporter, saying “I believe that had I been sent to the military academy, as my mother and father threatened; I would have been President a long time ago.”7

In this clip, we hear Mike admit that it was much harder to improve instruction than either he or Jerry Brown had anticipated. We heard, additionally in Installment 5, that the categorical programs–for which they had been the architects–now too often had the unintended consequence of tying the hands of local educational leaders. (See and listen to Installment 5 for details.) Accordingly, Mike notes, “The best thing that happened for both of us was for [Brown] to be Mayor of Oakland.”

So, this was a true turning point for Mike ideologically, and to some extent for Brown. Mike began to better understand the difficulties of improving instruction as he collaborated with his colleagues at CPRE. Let’s listen as Mike explains the importance of his CPRE research and collaboration:

Clip 2 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “I learned a lot from my colleagues at CPRE on the complexities of improving classroom instruction and from advising Brown, as Mayor of Oakland.” (Dick Jung, November 1, 2021, (45 seconds)8

Eight of Mike’s publications during this period are products from the CPRE project about mayors and education policy that Mike mentions at the end of this clip. Among them, a CPRE monograph: “Mayoral Influence, New Regimes, and Public School Governance.” It included analyses in several cities, including Boston, Chicago, and Cleveland, which had shifted governance structures to give more control to mayors in the hopes that such changes would ultimately lead to improved school quality and student achievement, as well as other benefits. The researchers concluded, however, upon closer examination, these attempts for giving more control of education to mayors were best understood within the broader context of a particular city. And “most importantly,” the CPRE researchers found that “it is difficult to link these governance shifts to improved instructional practices or outcomes.”9

Mike also emphasized in this clip the “intensive colleagueship” he felt with his fellow researchers at CPRE. We heard in the previous installment from two of them: Allan Odden, then at the University of Southern California, and Susan Fuhrman, Founder of CPRE.

Among Mike’s many projects at CPRE, the “Core Study” of various state-level education reforms over almost two decades influenced his thinking. Susan Fuhrman describes it:

Clip 3 (Audio): Susan Fuhrman: “We were engaged in a study…to look at the state education reforms in the eighties…called the ‘Core Study’… And Mike was in the group of us who were studying various states.” (Dick Jung, October 12, 2018, (58 seconds)10

Mike published seven pieces with Fuhrman and six with Odden during these years. Even today, he draws heavily from his CPRE work in his role now as a Senior Fellow in Residence for the Learning Policy Institute.

In League with Liu

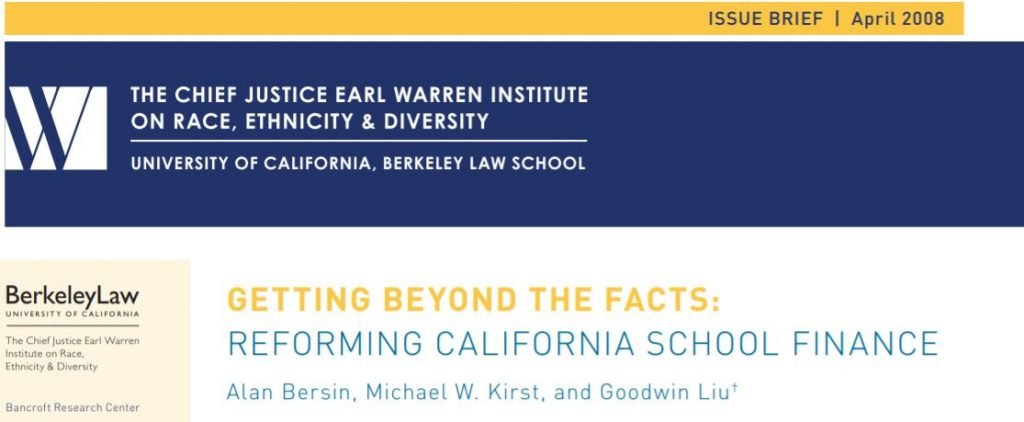

Cover of Issue Brief Mike co-authored. Photo Courtesy of University of California Berkeley Law School.

The “Local Control Funding Formula” was based largely on the ideas outlined…by Michael W. Kirst and his co-authors in Reforming California School Finance [in 2008]”11

In the area of K-12 policymaking, many note that Mike’s most significant research and writing during this period was an issue brief published in 2008 by the University of California’s Berkeley Law School. It was based on a major study of the finance and governance of California schools and co-authored with Godwin Liu, then Assistant Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Race, Ethnicity & Diversity at the UC Berkeley Law School, and Alan Bersin, then a member of the California State Board of Education and prior to that San Diego’s Superintendent of Public Schools and California’s Secretary of Education.

Mike had met GodwinLiu when he was a student in one or more of Mike’s education courses at Stanford. Liu, a biology major at the time, was a standout in Mike’s eyes, even then. During Liu’s stint in law school, he developed a strong interest in school finance and, after joining the UC Berkeley law faculty, still recalled Mike’s expertise and reputation on the topic. Mike knew Alan Bersin, first when Bersin served as San Diego’s Superintendent of Public Schools. When Mike and Liu decided to analyze California’s financing of its schools, Bersin was serving as California’s Education Secretary with Arnold Schwarzenegger as Governor.

Here is how Learning Policy Institute, a policy think tank, describes the state of school finance in California after the passage of Proposition 13 in 1978: “California policymakers stitched together a crazy quilt of a school finance system, with many separate categorical programs. Over time, it grew more complicated but failed to solve the inequalities that had prompted reform in the first place.”12 The researchers quote Mike’s 2007 assessment of the situation: “The result of California’s history is a finance system that has no coherent conceptual basis, is incredibly complex, fails to deliver an equal or equitable education to all children, and is a historical accretion.”13

Mike later provides more of a “boots-on-ground” assessment of the dire state of affairs in how California funds its public schools during a 2010 panel discussion at San Francisco’s Commonwealth Club. In this video clip from the meeting, he simplifies a bleak and complex situation:

Clip 4 (Video): Mike Kirst at “Keeping California’s Schools Competitive” panel, March 30, 2010. (2 minutes and 4 seconds)14

Mike comments on the plight of California’s funding of schools in 2010. Photo excerpted from YouTube video of this panel discussion.

Mike’s worry at the time was that he didn’t see that California had any “fundamental strategy to get out of [their] fiscal box.” He describes the situation in many school districts: “Now they’re beyond cutting counselors; they’re finished. Librarians are done; we’re finished with them. We got rid of music a long time ago. So, we’re down to the core.”

Another important part of this complexity that Mike and Jerry Brown experienced firsthand in Oakland was that a large portion of funding for the city’s public schools at the time came from more than 60 categorical programs for special populations of students or special programs.15 By the time Brown had finished his second term as Mayor in 2008, this categorical funding with a maze of requirements and constraints, stultifying the creativity of teachers and local school leaders, accounted for one-third of total education funding in California.16

And this was a time when the state’s total funding for schools was markedly declining.

A study “that was to shake things up”…Eventually

How bad was California’s school funding situation? That’s the rhetorical question EdSource journalist John Fensterwald posed to a group of high school students interested in policies affecting California education at a June 2021 “Summer Academy,” sponsored by Ed 100, a California education nonprofit. Let’s see how Fensterwald answers this question and how he portrays an underlying optimism from the Bersin, Kirst and Liu issue brief noted above:

Clip 5 (Video): John Fensterwald, narrator: “Funding fell 13 percent in 2007 (the year before these students started their schooling)…,” Stanford professor, Mike Kirst, looked at the disaster…(and) around 2008 he co-authored a study that was to shake things up…. (44 seconds)17

Picture of slide from John Fensterwald’s (EdSource’s Editor-at-Large), July 2021 presentation on California’s school finance system. Courtesy of EdSource.

Fensterwald explained to these students that Mike and his coauthors’ ideas to “create an equitable way to distribute money and give districts more control to spend it…didn’t get much attention or attraction at the time” and “would take years and a new governor, Jerry Brown, to become a reality.”

How that happened will be a central focus of the next installment of this multi-media biography. Before that, we now take a look at what Mike was also up to during these later interregnum years.

Mike’s “K-16 Era” Commences: 2000-2010

In his Autobiographical Reflections for the Stanford Emeriti Council (2014), Mike identifies the last decade of this interregnum period, that is between 2000 and 2010, as the start of his “K-16 Era.” He reflects on his first set of terms as State Board President, from 1997 to 1981, and his disappointment that he had rarely interacted with any of the major policymakers for California’s post-secondary education during all those years. We hear him lament the lack of communication between the K-12 and postsecondary sectors, observing it “has got to be hurting students.” Let’s listen in:

Clip 6 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “After my first term as State Board President, I began to wonder why higher K-12 and higher ed were so separate.” (Stanford Emeriti Council presentation, 40 seconds)18

In a recent conversation, Mike expands upon why he chose to focus on “broad access post-secondary education” as a special niche, starting around 2000 that he mentions at the end of this clip. Mike indicated that he and his colleague, Mike Usdan, had been quite influenced by a book entitled Colleges for Forgotten Americans. 19 In the short clip below, Mike explains why he became interested in researching and writing about this particular aspect of post-secondary education:

Clip 7 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “The problem in American higher education is in broad access; including community colleges.” (Dick Jung, January 14, 2022, 45 seconds)20

We hear Mike’s passion about what he calls the “colleges for forgotten Americans” when he concludes, “I’m not going to wring my hands about who doesn’t get into Stanford or Vanderbilt or something. These are trivial issues. The problem in American higher education is in broad access, including community colleges.”

In Mike’s introduction of Martha Kanter, the recipient of the Silicon Valley Foundation’s annual Pioneers and Purpose award in 2009, he elaborates on some of the reasons why he focused on the broad access to colleges, particularly the community college sector.

Clip 8 (Video): Mike Kirst, 2009: “Last year, fifty percent of our first-year students in the United States were in community colleges.” (YouTube video, 27 seconds)21

To delve into this relatively new and unexplored policy area of broad access post-secondary education, Mike began a program of self-education to understand the intersection of the two sectors of K-12 and postsecondary education. He began by auditing a graduate-level class at Stanford taught by Lew Mayhew, whose specialty was the American university system. Mike commented to me, “I’ve never done that with anybody else, you know, took their classes, because I didn’t know enough about it. I had no training in it. So I was looking for a way to enter the field.”22

Title slide from Silicon Valley Foundation’s 2009 award program honoring Martha Kanter. Picture excerpted from YouTube video.

He soon found that most of the academic scholarship and popular writing had been on selective colleges. He was convinced even further that broad access colleges would be an important “niche” for him to explore and it would hold great promise for helping a wide swath of American students.

At that time, Patricia Gumport, Director of Stanford Institute for Higher Education (SIHER), had received a grant from the U.S. Department of Education’s Center for Postsecondary Improvement. Mike proposed to her the idea of his looking in more detail at the transition from high school to higher education with a focus on broad access to post-secondary institutions. This included state colleges and community or junior colleges, for which so many students came unprepared academically, and accordingly had alarming drop-out rates. She agreed and provided the seed funding for his exploration of these issues.

“I knew California some, but I wanted to get in another setting,” Mike told me in a recent conversation. He took a visiting professorship at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, Illinois to further pursue this topic, explaining and partially joking, “because I wanted to get out a little bit from living in an urban area. You know, you get out into Champaign, and it’s all cornfields.”23

Mike began studying Illinois. Traveling to and studying at schools unknown to him, and to most Americans, such as Illinois State University at Normal and Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. Each of which had thousands of students enrolled. He analyzed and wrote about the problems of students’ poor preparation for college and the high drop-out rates at these open-access colleges. He soon expanded the funding for this work from his long-standing affiliations with CPRE, and from a new source, the Atlantic Philanthropies, located near CPRE in Philadelphia.

In this audio clip below, Mike speaks to the pivotal event when he received a large grant from this Philadelphia-based foundation:

Clip 9 (Audio): Mike Kirst: With funding from the Atlantic Philanthropies, “I was then able to hire Andrea (Venezia). And I was off to the races with their big grant.” (Dick Jung, January 14, 2022 (36 seconds)24

Andrea Venezia, Co-Director of The Bridge Project (1999-2003). Photo from SRI International website.

Chuck Feeney, a founder of Duty-Free Shoppes in the 1960s, is the person about whom Mike speaks of at the outset in this anecdote. The “Andrea” Mike names in this clip who “got him off to the races” in his K-16 period was Andrea Venezia. This was to become a pivotal relationship for both of them.

Andrea had earlier been an advisee of Mike as a master’s degree student in Stanford’s Administration and Policy Analysis in Higher Education program. After deciding she wanted to pursue a doctoral degree, she sought Mike’s advice for where best to do so. He encouraged her to apply to the doctoral program offered at the University of Texas at Austin’s Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs. Mike served on the committee for her Ph.D. dissertation, which examined undergraduate admissions policies in Central Texas high schools and middle schools.

As Mike tells this story: “It was a confluence of circumstances that, when Andrea was finishing her Ph.D. in Texas and wanted to come back to California, she contacted me. And that was exactly the time that I needed a research director for the grants I was hauling in. And so it was just timing that I offered it to her. And then, after that, we just worked together and were really very complementary.”25

The Stanford Univesity Bridge Project, as it was called, fielded the first large-scale national study documenting the state policy barriers that inhibited student progression from high school to college.26 As Mike noted, with Andrea as his partner in this endeavor, they were “off the to the races,” finding that researching and documenting the problems of transitioning from high schools to broad access institutions was “a real bell-ringer for funders.”27

The “publications” he mentioned at the end of this audio clip refer to nine citations in his current resume that he published between 2001 and 2018 with Andrea.28 They drew on their Bridge Project work and they distinguished Andrea–in addition to her many other scholarly accomplishments–as Mike’s most frequent co-author in this century, and one of his longest-standing colleagues and collaborators.

From the cover of the capstone 20003 publication of Stanford’s Bridge Project.

Andrea directed the research and publications of the project with Mike’s contributions and input, as he had lead responsibility in lining up additional funders. In March 2003, the Bridge Project released its policy report, Betraying the College Dream: How Disconnected K-12 and Postsecondary Education Systems Undermine Student Aspirations at the National Press Club. Mike has powerful memories of this event. Let’s listen in, as he begins, “I’ll never forget. This was our big breakthrough.”

Clip 10 (Audio): Mike Kirst: “It was one the earliest publications that was web-based. We got incredible amounts of downloads–tens of thousands.” (Dick Jung, January 14, 2022 (50 seconds)29

Mike considers this event and the response the report received, as we’ve heard, as “the signal shot” that “launched us big-time” and fueled the project with additional funding from Pew Charitable Trusts, the U.S. Department of Education, as well as follow-up grants from the Atlantic Philanthropies.

The “complementary” nature of Mike and Andreas’ professional endeavors in researching and reporting on the disjunctures between America’s elementary and secondary schools, and the post-secondary sector, is also fully reflected in Andrea’s resume. Mike and she co-edited a book, From High School to College; a book chapter, “The Case for Improving Connections Between K-16 Schools and Colleges: Improving Access to Postsecondary Education”; and literally a dozen other publications, occasionally with others, including Mike Usdan and Pat Callan.30They were frequent presenters together at scores of professional meetings, including at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. (cited above).

Andrea led the California State University’s Student Success Network for years, a systemwide network that brings faculty, students, and leaders to advance equitable student learning and success. Additionally, she led the California Education Policy Fellowship Program, part of a national program sponsored by the Institute for Educational Leadership, led for many years by Mike Usdan.31

To conclude this installment, let’s listen to Andrea’s summary of important traits in Mike she admires from working with him so closely, and her advice to the students in the fellow’s program she ran:

Clip 11 (Audio): Andrea Venezia: “I just pound it into the (Education Policy) Fellow all the time, ‘Be like Mike.'” (Dick Jung, September 19, 2018, (40 seconds)32

Andrea emphasizes Mike’s ability to bridge the gap between academics and policymaking, his soundbites, and being that “rare bird who can speak in the regular language to people and explain things without having all the answers.” These sorts of observations from so many underlie our conviction that this biography, which incorporates various media, can help Mike come alive for a broad audience.

We will be hearing from Andrea and others in the upcoming installments about more sides of Mike, some of which might understandably be considered as challenges and trade-offs for an uncommon academic. We will also examine in the next installment what many consider to be his most significant contributions to improving the educational opportunities for our county’s children who are the most in need.33

Stay tuned.

Editor’s Note: The Appendix for “Conversations With and About Mike” contains transcripts for the recorded audio and video clips. To view the Audio Transcripts go to this page >

Footnotes

- Definition from Oxford Languages: noun 1. a period when normal government is suspended, especially between successive reigns or regimes. 2. an interval or pause between two periods of office or other things.

- Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

- “Jerry Brown’s years as Oakland mayor set stage for political comeback.” San Jose Mercury News. August 29, 2010.

- “Jerry Brown’s years as Oakland mayor set stage for political comeback.” San Jose Mercury News. August 29, 2010.

- Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

- The charter school’s full name: The Oakland Military Institute College Preparatory Academy.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerry_Brown

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, November 1, 2021.

- Kirst, M.W. (2002). Mayoral Influence, New Regimes, and Public School Governance. Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

- Susan Fuhrman interview with the author, October 12, 2018.

- Furger, R. C., Hernández, L. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The California Way: The Golden State’s quest to build an equitable and excellent education system. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, p. 13. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/california-way-equitable-excellent-education-system

- Furger, R. C., Hernández, L. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The California Way: The Golden State’s quest to build an equitable and excellent education system. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, p. 5. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/california-way-equitable-excellent-education-system

- Furger, R. C., Hernández, L. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The California Way: The Golden State’s quest to build an equitable and excellent education system. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, p. 5. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/california-way-equitable-excellent-education-system

- California Schools Panel Commonwealth Club of California. “Keeping California’s Schools Competitive: Can Today’s Students Become Tomorrow’s Leaders?” Part of the Chevron California Innovation Series. California Schools Panel (3/31/10) – YouTube.

- For a definition of “categorical programs” see: https://edsource.org/glossary/categorical-aid-categorical-programs

- Furger, R. C., Hernández, L. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The California Way: The Golden State’s quest to build an equitable and excellent education system. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute, p. 6. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/california-way-equitable-excellent-education-system

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DrQB63VkWcY

- Mike Kirst’s Autobiographical Reflections, June 9, 2014, presentation for the Stanford Emeriti Council. Republished February 5, 2015, by Stanford’s Center for Education Policy Analysis. https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/nc116hr7647

- 19 Mike slightly misstates the title of this book by Edgar Alden Dunam. The actual, full title is Colleges of the Forgotten Americans: A Profile of State Colleges and Regional Universities. McGraw Hill. 1969.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- Mike Kirst introducing Kantor. https://vimeo.com/674490383/10af2bbf5f, 2009

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- https://www.sri.com/bios/andrea-venezia/

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- There are nine publications in Mike’s current resume that he coauthored with Andre Venezia (and sometimes others).

- Mike Kirst interview with the author, January 14, 2022.

- Patrick Callan at the time was the President of the Higher Education Policy Institute which published a newsletter CROSSTALK that Mike Kirst feels helped broaden the impact of his and Andrea Venezia’s K16 research and publications.

- Andrea Venezia’s unpublished resume, Policy. https://www.csus.edu/faculty/v/venezia/

- Andrea Venezia interview with the author, September 19, 2018.

- Mike discusses some of his other state and federal policy activities during this period: Mike Kirst interview with Anita Hecht, November 19, 2013, for The New York Archives: States’ Impact on Federal Education Policy Oral History Project, including these details: “I was still involved heavily with state policy, some federal policy. I chaired a national research council panel on international comparisons of education; another one on the National Assessment of Educational Progress [NAEP]. I worked for them. I worked a lot for the US departments, particularly when there were Democrats in, on administrative issues –making Title I more effective. Wrote a lot about federal aid and so on.” p. 11 of transcript.